In recent years much of the spotlight in AI has been on big models: large language models (LLMs) with billions or even trillions of parameters, trained on massive data sets, achieving superhuman performance in many tasks. But the question remains: is scale everything? Can thoughtful architecture and training design yield strong performance even with far fewer parameters?

That is precisely the question Less is More: Recursive Reasoning with Tiny Networks (Jolicoeur-Martineau, 2025) paper addresses. It shows that a very small neural network, only ~7 million parameters, can compete or exceed large models on challenging “reasoning” benchmarks (structured tasks like puzzles) by using a form of recursive reasoning. The key idea: you don’t necessarily need more layers or more width, you can ask a small model to think again, refine its answer, rather than simply predict once.

Specifically, the work benchmarks itself on tasks such as the ARC-AGI benchmark (Abstract Reasoning Corpus for “general intelligent” reasoning), as well as Sudoku and Maze tasks, which are deliberately chosen because they require pattern recognition + structured reasoning rather than plain language modelling. The results are noteworthy.

Thus this paper delivers a compelling message: less can be more, if the architecture encourages iterative refinement, self-correction, and generalization rather than straight memorisation.

The conceptual core: recursive refinement

At a conceptual level the paper contrasts two styles of reasoning architectures:

-

One-shot prediction: A network sees input , computes an answer , and training tries to make in one forward pass. Many standard architectures follow this. Large models may embed chain-of-thought or sampling strategies, but largely they rely on one pass (or several independent passes) rather than a tightly coupled iterative refinement.

-

Recursive reasoning (iterative refinement): A network starts with an initial answer guess (perhaps trivial), then repeatedly refines its internal state and its answer guess through a loop:

After iterations we output . Training uses supervision at multiple intermediate steps (deep supervision) so that each intermediate is encouraged to be closer to the target. This lets the network learn how to refine its answer rather than simply what the answer is.

The paper builds on earlier work called the Hierarchical Reasoning Model (HRM), which used two small networks recursing at different frequencies (a “low-level” module and a “high-level” module) in a biologically-inspired dual-timing loop.

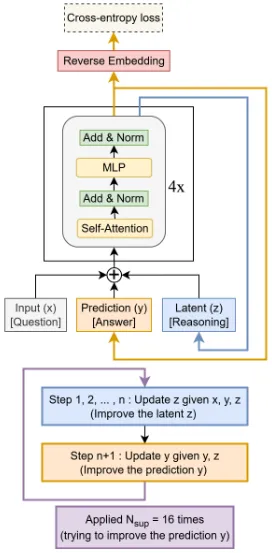

But the novel contribution here is the Tiny Recursive Model (TRM), which strips the architecture down to a single network (two layers) that simply loops, refining its latent reasoning state and the current output. No dual modules, no fixed-point approximations, no separation of frequencies. It is elegantly minimalist, and yet the experiments show this suffices (and even outperforms more complex designs).

Mathematical formulation

Inputs and variables

- denotes the input question or puzzle (e.g., a grid, maze description).

- is the model’s current answer/solution estimate at iteration .

- is the model’s internal latent “reasoning state” at iteration .

- is the ground truth target answer.

Update rules For :

Here and are parameterized (the same small network may implement both roles). In code the authors simplify by combining into one “tiny network” that takes and outputs a refined .

Loss function (deep supervision) Rather than only enforce loss on the final output , the training pushes every intermediate towards . For example:

where is the cross-entropy loss, and is a small additional term for a halting head: a learned scalar/logit at each iteration that predicts “should I stop refining?” This lets the model skip further loops if a correct answer is already reached.

Architecture choices

- In TRM the network is 2 layers (e.g., two Transformer or MLP blocks) and total parameters ~7 M.

- Empirically the authors find: increasing depth or width worsened generalization (overfitting) on the small data regimes they use.

- On small fixed-size grid tasks (like Sudoku) they found a plain MLP (with sequence flattening) worked better than self-attention. On larger or variable size inputs, self-attention remains useful.

- They use Exponential Moving Average (EMA) of parameters for stability and improved generalization.

Recursion vs parameter expansion trade-off A key mathematical insight: Recursion allows a small network to behave like a deeper network, effectively “unrolling” many layers via time instead of width/depth in space. For example, iterating times of a 2-layer network is analogous to a -layer deep network, except each “layer” shares parameters (the same small net reused) and training enforces intermediate correctness. This parameter sharing reduces overfitting risk and allows training on fewer examples.

Experimental highlights

- On the Sudoku-Extreme benchmark the TRM model achieved around 87% accuracy, compared to ~55% with the prior HRM approach.

- On Maze-Hard the performance was ~85%.

- On the ARC-AGI benchmark: for the “ARC-AGI-1” subset they obtained ~45% accuracy; for the tougher “ARC-AGI-2” they report ~8%. These numbers surpass many LLM baselines with orders of magnitude more parameters.

- Key ablations: deeper networks (4 layers or more) decreased generalization; dual-network hierarchies (as in HRM) did not help; the halting mechanism could be simplified; recursion depth (number of iterations) mattered significantly; data augmentation and EMA helped.

Conclusion

The Tiny Recursive Model transforms reasoning into an iterative, self-corrective process. Instead of producing a single answer, the network repeatedly refines its prediction, fixing earlier errors and improving with each pass. Because the same small network is reused at every step, it achieves strong generalization with very few parameters, avoiding overfitting on limited data. Deep supervision teaches the model not only to find the correct answer but also to learn how to reach it, while recursion provides effective depth without the cost of a larger architecture. The key insight is that simplicity, one small recurrent loop, is more efficient than complex, multi-network designs.

Still, the approach remains confined to structured, grid-based problems like Sudoku or ARC. Its scalability to open-ended reasoning or larger datasets is untested, and recursive training increases memory demands. The halting mechanism and theoretical foundations also need refinement. Comparisons with large language models should be seen cautiously, as they address different tasks.

This line of work suggests that future AI systems could emphasize algorithmic structure over size. Recursive refinement and parameter sharing may lead to lightweight, deployable reasoning models and inspire new ways for large models to “think iteratively” rather than only forward once.